Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Mild to Moderate Head Injuries in Children

Guideline | About the Guideline | Guideline Working Group Members | Guideline Questions | Consulting Organizations | Endorsements | Manuscript and Methodology Links | Education Modules | Press Inquiries and Media

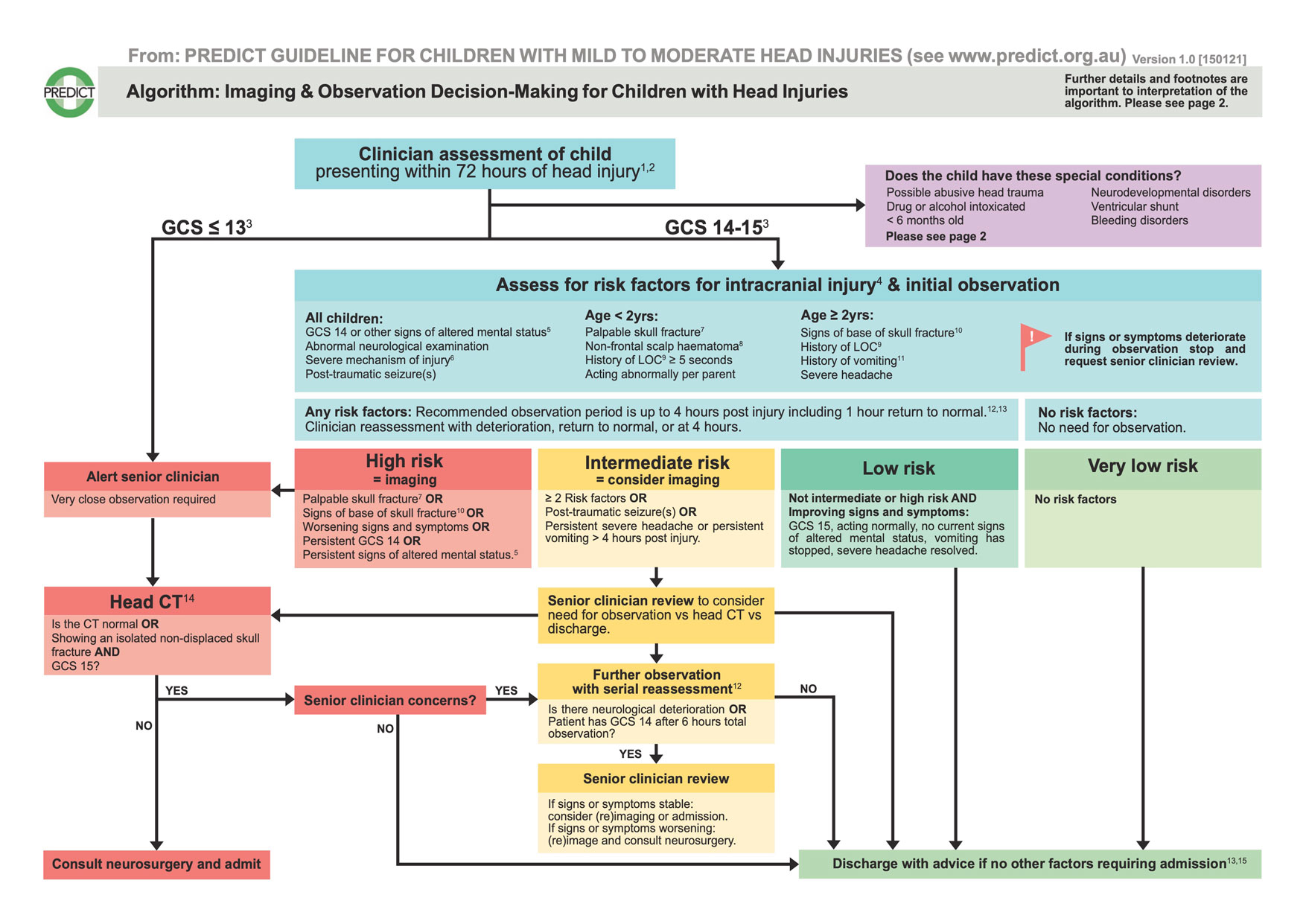

Children frequently present with head injuries to acute care settings. Led by PREDICT (Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative), a multidisciplinary working group developed the first Australian and New Zealand guideline for mild to moderate head injuries in children. Addressing 33 key clinical questions, it contains 71 recommendations, and an imaging/observation algorithm. The Guideline provides evidence-based, locally applicable, practical clinical guidance for the care of children with mild to moderate head injuries presenting to acute care settings.

The Guideline recommendations and algorithm are presented in a drop-down menu below and can be downloaded in three documents; (1) a detailed Full Guideline summarising the evidence underlying each recommendation, (2) a Guideline Summary, and (3) a clinical Algorithm on Imaging and Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries.

Disclaimer: The PREDICT Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Mild to Moderate Head injuries in Children aims to combine a review of the available evidence for the management of mild to moderate head injuries in children with current clinical and expert practice and develop general clinical practice recommendations based on the best evidence available at the time of publication. The content provided is not intended to replace personal consultation with, diagnosis and treatment by a qualified health care professional. Care should always be based on professional medical advice, appropriate for a patient’s specific circumstances.

Download the Summary of Guideline

Download the Algorithm

The PREDICT Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-Making for Children with Head Injuries accompanies the PREDICT Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Mild to Moderate Head injuries in Children. It incorporates the core imaging and observation guideline recommendations for use by clinicians assessing a child with head injury in an acute care setting. This video provides an introduction to the algorithm and how it can be used during clinician decision-making.

Recommendations

Evidence-Informed Recommendation (EIR)

Recommendation formulated with evidence from source guideline and/or PREDICT literature search

Consensus-Based Recommendation (CBR)

Recommendation formulated by consensus, where evidence was sought but none was identified, or where the identified evidence was limited by indirectness

Practice Point (PP)

A recommendation that is outside the scope of the evidence search and is based on consensus.

Each recommendation is classed as new (i.e. created by the Guideline Working Group), adopted (i.e. taken from existing guidelines) or adapted (i.e. adapted from existing guidelines).

| 1 | CBR | Children with head injury should be assessed in a hospital setting if the mechanism of injury was severe1 or if they develop the following signs or symptoms within 72 hours of injury:

| New |

| 2 | CBR | Children with trivial head injury4 do not need to attend hospital for assessment; they can be safely managed at home.3 | New |

| 3 | EIR | Consultation with a neurosurgical service may not be routinely required for infants and children with an isolated, non-displaced, linear skull fracture on a head CT scan without intracranial injury and a GCS score of 15.5 | New |

| A | PP | Children aged less than 2 years with a suspected or identified isolated, non-displaced, linear skull fracture should have a medical follow-up within 1–2 months to assess for a growing skull fracture.6 | New |

| B | PP | In all children presenting with mild to moderate head injury, the possibility of abusive head trauma should be considered. | New |

| 4 | CBR | Consultation with a neurosurgical service should occur in all cases of intracranial injury or skull fracture shown on a head CT scan, other than in infants and children with an isolated, non-displaced, linear skull fracture on a head CT scan without intracranial injury and a GCS score of 15.5 | Adapted |

2 A case of a single isolated vomit can be assessed in general practice.

3 In children aged less than 2 years the signs of intracranial injury may not be apparent in the first hour.

4 Trivial head injury includes ground-level falls, and walking or running into stationary objects, with no loss of consciousness, a GCS score of 15 and no signs or symptoms of head trauma other than abrasions.

5 Measured using an age-appropriate GCS.

6 A growing skull fracture is a rare complication of linear skull fractures. It can occur in children aged less than 2 years with a skull bone fracture, and it represents the diastatic enlargement of the fracture due to a dural tear, with herniating brain tissue or a cystic cerebrospinal fluid-filled mass underneath. In the setting of a known skull fracture, a growing fracture is indicated by any of the following: persistent boggy swelling along a fracture line; palpable diastasis; an enlarging, asymmetrical head circumference; or delayed onset neurological symptoms. This can be assessed by a neurosurgeon, paediatrician or GP who is able to assess for a growing skull fracture.

| 5 | EIR | In children with mild to moderate head injury and a GCS score of 14–155 who have one or more risk factors for a clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see below or Box A for risk factors, and Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries), clinicians should take into account the number, severity and persistence of signs and symptoms, and family factors (e.g. distance from hospital and social context) when choosing between structured observation and a head CT scan.8 Risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury:7

Specific risk factors for children aged less than 2 years:

Specific risk factors for children aged 2 years and older:

| New |

| 6 | EIR | For children presenting to an acute care setting within 24 hours of a head injury and a GCS score of 155, a head CT scan should not be performed without any risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors, and Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries) | New |

| 7 | EIR | Children presenting to an acute care setting within 72 hours of a head injury and a GCS score of 13 or less5 should undergo an immediate head CT scan.8 | New |

| 8 | CBR | Children with delayed initial presentation (24–72 hours after head injury) and a GCS score of 155 should be risk stratified in the same way as children presenting within 24 hours. | New |

| C | PP | For children with mild to moderate head injury, consider shared decision-making14 with parents, caregivers and adolescents (e.g. a head CT scan8 or structured observation). | New |

| D | PP | All cases of head injured infants aged 6 months and younger should be discussed with a senior clinician. These infants should be considered at higher risk of intracranial injury, with a lower threshold for observation or imaging.8 | New |

5 Measured using an age-appropriate GCS.

6 A growing skull fracture is a rare complication of linear skull fractures. It can occur in children aged less than 2 years with a skull bone fracture, and it represents the diastatic enlargement of the fracture due to a dural tear, with herniating brain tissue or a cystic cerebrospinal fluid-filled mass underneath. In the setting of a known skull fracture, a growing fracture is indicated by any of the following: persistent boggy swelling along a fracture line; palpable diastasis; an enlarging, asymmetrical head circumference; or delayed onset neurological symptoms. This can be assessed by a neurosurgeon, paediatrician or GP who is able to assess for a growing skull fracture.

7 Clinically-important traumatic brain injury is defined as death from traumatic brain injury, neurosurgical intervention for traumatic brain injury, intubation for more than 24 hours for traumatic brain injury, or hospital admission of 2 nights or more associated with traumatic brain injury on CT.

8 Sedation is usually not required in children for non-contrast CT scans as they generally only take seconds to complete. If sedation is required for uncooperative children requiring imaging local safe sedation practice should be followed.

9 Agitation, drowsiness, repetitive questioning, slow response to verbal communication.

10 Palpable skull fracture: on palpation or possible on the basis of swelling or distortion of the scalp.

11 Non-frontal scalp haematoma: occipital, parietal or temporal.

12 Signs of base of skull fracture: haemotympanum, ‘raccoon eyes’, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhoea or CSF rhinorrhoea, Battle’s signs.

13 Isolated vomiting, without any other risk factors, is an uncommon presentation of clinically-important traumatic brain injury. Vomiting, regardless of the number or persistence of vomiting, in association with other risk factors increases concern for clinically-important traumatic brain injury.

14 Validated tools should be adapted for shared decision-making with parents, caregivers and adolescents.

| 9 | EIR | In children with a ventricular shunt (e.g. ventriculoperitoneal shunt) presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, who have no risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors), consider structured observation over an immediate head CT scan. | Adapted |

| E | PP | In children with a ventricular shunt and mild to moderate head injury, consider obtaining a shunt series, based on consultation with a neurosurgical service, if there are local signs of shunt disconnection, shunt fracture (e.g. palpable disruption or swelling), or signs of shunt malfunction. | New |

| 10 | EIR | In children with congenital or acquired bleeding disorders, following a head injury that results in presentation to an acute care setting, where there are no risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors, and Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries), consider structured observation over an immediate head CT scan. If there is a risk factor for intracranial injury, a head CT should be performed. If there is a deterioration in neurological status, a head CT should be performed urgently. | Adapted |

| F | PP | In children with coagulation factor deficiency (e.g. haemophilia), following a head injury that results in presentation to an acute care setting, the performance of a head CT scan or the decision to undertake structured observation must not delay the urgent administration of replacement factor. | New |

| G | PP | In all children with a bleeding disorder or on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, following a head injury that results in presentation to an acute care setting, clinicians should urgently seek advice from the haematology team treating the child in relation to risk of bleeding and management of the coagulopathy. | New |

| 11 | CBR | In children with immune thrombocytopaenias, following a head injury which results in presentation to an acute care setting, where there are no risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors, and Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries), consider structured observation over an immediate head CT scan. If there is a risk factor for intracranial injury, a head CT should be performed. If there is a deterioration in neurological status, a head CT should be performed urgently. Clinicians should check a platelet count in all children with immune thrombocytopaenias, and blood group in all symptomatic patients, if not already available. | Adapted |

| H | PP | In children with immune thrombocytopaenia with mild to moderate head injury and platelet counts of less than 20 × 109/L, consider empirical treatment after discussion with the haematology team treating the child. | New |

| 12 | EIR | In children with mild to moderate head injury on warfarin therapy, other anticoagulants (e.g. direct oral anticoagulants) or antiplatelet therapy, consider a head CT scan regardless of the presence or absence of risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors, and Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries). Seek senior clinician review to inform timing of the head CT scan. Discuss the patient with the team managing the anticoagulation regarding early consideration of reversal agents. Check the appropriate anticoagulant measure (if available); for example, international normalised ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) or anti-Xa assay. | Adapted |

| I | PP | In adolescents with mild to moderate head injury and taking anticoagulants, including warfarin, consider managing according to adult literature and guidelines. | New |

| 13 | CBR | It is unclear whether children with neurodevelopmental disorders presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury have a different background risk for intracranial injury. Consider structured observation or a head CT scan for these children because they may be difficult to assess. For these children, shared decision-making with parents, caregivers and the clinical team that knows the child is particularly important. | New |

| 14 | CBR | In children who are drug or alcohol intoxicated presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, treat as if the neurological findings are due to the head injury. The decision to undertake structured observation or a head CT scan should be informed by the risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors, and Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-making for Children with Head Injuries) rather than the child being intoxicated. | New |

| 15 | EIR | In children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, the risk of clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 requiring hospital care is low enough to warrant discharge home without a head CT scan if the patient has no risk factors for a clinically important traumatic brain injury7 (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors), has a normal neurological examination and has no other factors warranting hospital admission (e.g. other injuries, clinician concerns [e.g. persistent vomiting], drug or alcohol intoxication, social factors, underlying medical conditions such as bleeding disorders or possible abusive head trauma) | New |

| J | PP | In children undertaking structured observation following mild to moderate head injury, consider observation up to 4 hours from the time of injury, with discharge if the patient returns to normal for at least 1 hour. Consider an observation frequency of every half hour for the first 2 hours, then 1-hourly until 4 hours post injury. After 4 hours, continue observation at least 2-hourly for as long as the child remains in hospital. | Adapted |

| K | PP | The duration of structured observation may be modified based on patient and family variables, including time elapsed since injury or signs and symptoms, and reliability and ability of the child or parent to follow advice on when to return to hospital. | New |

| 16 | EIR | After a normal initial head CT scan in children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, the clinician may conclude that the risk of clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 requiring hospital care is low enough to warrant discharge home, provided that the child has a GCS score of 15,5 normal neurological examination and no other factors warranting hospital admission (e.g. other injuries, clinician concerns [e.g. persistent vomiting], drug or alcohol intoxication, social factors, underlying medical conditions such as bleeding disorders or possible abusive head trauma) | Adapted |

| L | PP | The duration of structured observation for children with mild to moderate head injury who have a normal initial head CT scan but do not meet discharge criteria should be based on individual patient circumstances. Consider an observation frequency of every half hour for the first 2 hours, then 1-hourly until 4 hours post injury. After 4 hours, continue at least 2-hourly for as long as the child remains in hospital. | New |

7 Clinically-important traumatic brain injury is defined as death from traumatic brain injury, neurosurgical intervention for traumatic brain injury, intubation for more than 24 hours for traumatic brain injury, or hospital admission of 2 nights or more associated with traumatic brain injury on CT.

| 17 | EIR | After a normal initial head CT scan in children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, neurological deterioration should prompt urgent reappraisal by the treating clinician, with consideration of an immediate repeat head CT scan and consultation with a neurosurgical service. Children who are being observed after a normal initial head CT scan15 who have not achieved a GCS score of 155 after up to 6 hours observation from the time of injury, should have a senior clinician review for consideration of a further head CT scan or MRI scan and/or consultation with a neurosurgical service. The differential diagnosis of neurological deterioration or lack of improvement should take account of other injuries, drug or alcohol intoxication and non-traumatic aetiologies. | Adapted |

15The initial head CT scan should be interpreted by a radiologist to ensure no injuries were missed.

| 18 | EIR | In children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury where abusive head trauma is suspected, a head CT scan should be used as the initial diagnostic tool to evaluate possible intracranial injury and other injuries (e.g. skull fractures) relevant to the evaluation of abusive head trauma. The extent of the assessment should be coordinated with the involvement of an expert in the evaluation of non-accidental injury. | Adapted |

| M | PP | Detection of skull fractures, even in the absence of other intracranial injury, is important in cases of suspected abusive head trauma. | New |

| 19 | EIR | In children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, clinicians should not use plain X-rays of the skull prior to, or in lieu of, a head CT scan to diagnose skull fracture or to determine the risk of intracranial injury. | Adapted |

| 20 | EIR | In children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, clinicians should not use ultrasound of the skull prior to, or in lieu of, a head CT scan to diagnose or determine the risk of intracranial injury. | Adapted |

| 21 | EIR | In infants presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, clinicians should not use transfontanelle ultrasound prior to, or in lieu of, a head CT scan to diagnose intracranial injury. | Adopted |

| 22 | EIR | In children presenting to an acute care setting following mild to moderate head injury, for safety, logistical and resource reasons, MRI should not be routinely used for primary investigation of clinically-important traumatic brain injury.16 | Adopted |

| N | PP | In certain settings with the capacity to perform MRI rapidly and safely in children, MRI may be equivalent to a head CT scan in terms of utility. | New |

| 23 | EIR | In infants and children with mild to moderate head injury, presenting to an acute care setting, healthcare professionals should not use biomarkers to diagnose or determine the risk of intracranial injury outside of a research setting. | Adopted |

| 24 | EIR | In children with head injury, radiation dose should be optimised for head CT scans, with the primary aim being to produce diagnostic quality images that can be interpreted by the radiologist and are sufficient to demonstrate a small volume of intracranial haemorrhage (e.g. thin-film subdural haematoma). | New |

| 25 | EIR | Age-based CT scanning protocols that are optimised and as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) for a paediatric population should be used. | New |

| 26 | EIR | Soft tissue and bone algorithm standard thickness and fine-slice images and multiplanar 2D and bony 3D reconstructions should be acquired, archived and available to the radiologist for review at the time of initial interpretation. | New |

| 27 | CBR | Cervical spine imaging should not be routine in all children with mild to moderate head injury who require imaging. | New |

| 28 | CBR | Children presenting within 72 hours of a mild to moderate head injury can be safely discharged into the community if they meet all the following criteria:

| Adapted |

| 29 | CBR | Children presenting within 72 hours of a mild to moderate head injury, and deemed appropriate for discharge with respect to low risk of a clinically-important traumatic brain injury7 should be discharged home according to local clinical practice regarding their ability to return to hospital (in terms of distance, time, social factors and transport). | Adapted |

| 30 | CBR | Children discharged from hospital after presenting within 72 hours of a mild to moderate head injury should have a suitable person at home to supervise them for the first 24 hours post injury. | Adapted |

| 31 | EIR | All parents and caregivers of children discharged from hospital after presenting within 72 hours of a mild to moderate head injury should be given clear, age-appropriate, written and verbal advice on when to return to the emergency department; this includes worsening symptoms (e.g. headache, confusion, irritability, or persistent or prolonged vomiting), a decreased level of consciousness or seizures. | Adopted |

| 32 | EIR | All parents and caregivers of children discharged from hospital after presenting within 72 hours of mild to moderate head injury should be given contact information for the emergency department, telephone advice line or other local providers of advice. | Adopted |

| 33 | EIR | All parents and caregivers of children discharged from hospital after presenting within 72 hours of mild to moderate head injury should be given clear, age-appropriate written and verbal advice on the possibility of persistent or delayed post-concussive symptoms, and the natural history (including the recovery process) of post-concussive symptoms in children. | Adopted |

| 34 | EIR | All parents and caregivers of children discharged from hospital after presenting within 72 hours of mild to moderate head injury should be given clear, age-appropriate written and verbal advice on exercise, return to sport, return to school, alcohol and drug use, and driving. | Adopted |

| 35 | EIR | Children presenting within 72 hours of a mild to moderate head injury deemed at low risk of a clinically-important traumatic brain injury,7 as determined by any of the following – a negative head CT scan, structured observation or the absence of risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury (see PREDICT Recommendation 5 or Box A for risk factors) – do not require specific follow-up for an acute intracranial lesion (e.g. bleeding). | New |

| 36 | EIR | All parents and caregivers of children discharged from hospital after presenting within 72 hours of mild to moderate head injury should be advised that their child should attend primary care 1–2 weeks post injury for assessment of post-concussive symptoms and to monitor clinical status. | New |

| 37 | EIR | In children at high risk of persistent post-concussive symptoms (more than 4 weeks) (see Practice point O), clinicians should consider provision of referral to specialist services for post-concussive symptom management. | Adapted |

| O | PP | For children presenting within 72 hours of mild to moderate head injury, emergency department clinicians should consider factors known to be associated with an increased risk of developing post-concussive symptoms. Examples include, but are not restricted to, a high degree of symptoms at presentation, girls aged over 13 years, previous concussion with symptoms lasting more than a week, or past history of learning difficulties or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). There are validated prediction rules (e.g. Predicting Persistent Post-concussive Problems in Pediatrics (5P) clinical risk score) or risk tables to provide prognostic counselling and follow-up advice to children and their caregivers on their potential risk of developing post-concussive symptoms (see Tables 6.3.3 and 6.3.4 in full Guideline for further details). | New |

| 38 | EIR | In children whose post-concussive symptoms do not resolve within 4 weeks, clinicians should provide or refer the child to specialist services for persistent post-concussive symptom management. | Adapted |

7 Clinically-important traumatic brain injury is defined as death from traumatic brain injury, neurosurgical intervention for traumatic brain injury, intubation for more than 24 hours for traumatic brain injury, or hospital admission of 2 nights or more associated with traumatic brain injury on CT.

| 39 | CBR | Children with mild to moderate head injury should not return to contact sport until they have successfully returned to school. Early introduction (after 24 hours) of gradually increasing, low to moderate physical activity is appropriate, provided it is at a level that does not result in exacerbation of post-concussive symptoms. | Adapted |

| 40 | CBR | Children with post-concussive symptoms should avoid activities with a risk of contact, fall or collisions that may increase the risk of sustaining another concussion during the recovery period. | Adapted |

| 41 | CBR | Children with post-concussive symptoms who play sport should commence a modified non-contact exercise program and must subsequently be asymptomatic before full contact training or game day play can resume. | Adapted |

| P | PP | A modified non-contact exercise program can be supervised by a parent (for younger children) or sports or health personnel (for children with ongoing significant symptoms or older children wanting to resume contact sport). | New |

| 42 | EIR | Children with mild to moderate head injury should have a brief period of physical rest post injury (not more than 24–48 hours post injury). | Adapted |

| 43 | EIR | Following a mild to moderate head injury, children should be introduced to early (between 24 and 48 hours post injury), gradually increasing, low to moderate physical activity, provided that it is at a level that does not result in significant exacerbation of post-concussive symptoms. Physical activities that pose no or low risk of sustaining another concussion can be resumed whenever symptoms improve sufficiently to permit activity, or even if mild residual post-concussive symptoms are present. | Adapted |

| 44 | EIR | Children with mild to moderate head injury should have a brief period of cognitive rest17 post injury (not more than 24–48 hours post injury). | New |

| 45 | EIR | Following a mild to moderate head injury, children should be introduced to early (between 24 and 48 hours post injury), gradually increasing, low to moderate cognitive activity, at a level that does not result in significant exacerbation of post-concussive symptoms. | New |

| 46 | EIR | Children with post-concussive symptoms should gradually return to school at a level that does not result in significant exacerbation of post-concussive symptoms. This may include temporary academic accommodations and temporary absences from school. | Adapted |

| 47 | EIR | All schools should have a concussion policy that includes guidance on sport-related concussion prevention and management for teachers and staff, and should offer appropriate short-term academic accommodations and support to students recovering from concussion. | Adopted |

| 48 | EIR | Clinicians should assess risk factors and modifiers that may prolong recovery and may require more, prolonged or formal academic accommodations. In particular, adolescents recovering from concussion may require more academic support during the recovery period. | Adopted |

| Q | PP | Protocols for return to school should be personalised and based on severity of symptoms, with the goal being to increase student participation without exacerbating symptoms. Academic accommodations and modifications after concussion may include a transition plan and accommodations designed to reduce demands, monitor recovery and provide emotional support (see Box B). | New |

| 49 | CBR | Following a mild to moderate head injury, children’s use of screens should be consistent with the recommendation for gradually increasing, low to moderate cognitive activity; that is, activity at a level that does not result in significant exacerbation of post-concussive symptoms. | New |

| R | PP | Parents and caregivers should be aware of general recommendations for screen use in children aged 2–5 years; that is, limiting screen use to 1 hour per day, no screens 1 hour before bed, and devices to be removed from bedrooms before bedtime. | New |

| S | PP | Parents and caregivers should be aware of general recommendations for screen use in children aged over 5 years; that is, promote that children get adequate sleep (8–12 hours, depending on age), recommend that children not sleep with devices in their bedrooms (including TVs, computers and smartphones) and avoid exposure to devices or screens for 1 hour before bedtime. | New |

| 50 | CBR | Adolescents (and children as appropriate) who have had a mild to moderate head injury causing loss of consciousness must not drive a car, motorbike or bicycle, or operate machinery for at least 24 hours. | New |

| 51 | CBR | Adolescents (and children as appropriate) who have had a mild to moderate head injury should not drive a car or motorbike, or operate machinery until completely recovered or, if persistent post-concussive symptoms are present, until they have been assessed by a medical professional. | New |

| 52 | CBR | Children diagnosed with a repeat concussion soon after the index injury (within 12 weeks) or after multiple repeat episodes are at increased risk of persistent post-concussive symptoms. Parents and caregivers of children with repeat concussion should be referred for appropriate medical review (e.g. to a paediatrician). | New |

| Box A | Head injury risk factors for clinically-important traumatic brain injury1 | |

|---|---|

|

|

Age less than 2 years

| Age 2 years or older

|

1 Clinically-important traumatic brain injury is defined as death from traumatic brain injury, neurosurgical intervention for traumatic brain injury, intubation for more than 24 hours for traumatic brain injury, or hospital admission of 2 nights or more associated with traumatic brain injury on CT.

2 Measured using an age-appropriate GCS.

3 Other signs of altered mental status: agitation, drowsiness, repetitive questioning, slow response to verbal communication.

4 Severe mechanism of injury: motor vehicle accident with patient ejection, death of another passenger or rollover; pedestrian or bicyclist without helmet struck by motorised vehicle; falls of 1 m or more for children aged less than 2 years and more than 1.5 m for children aged 2 years or older; or head struck by a high-impact object.

5 Palpable skull fracture: on palpation or possible on the basis of swelling or distortion of the scalp.

6 Non-frontal scalp haematoma: occipital, parietal or temporal.

7 Signs of base of skull fracture: haemotympanum, ‘raccoon’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhoea or CSF rhinorrhoea, Battle’s signs

8 Isolated vomiting, without any other risk factors, is an uncommon presentation of clinically important traumatic brain injury. Vomiting, regardless of the number of vomits or persistence of vomiting, in association with other risk factors increases concern for clinically-important traumatic brain injury.

| Box B | Examples of academic accommodations and modifications that may be used following concussion to facilitate increasing school participation without exacerbating symptoms |

|---|

Transition plan

|

Accommodations designed to reduce demands, monitor recovery and provide emotional support

|

Additional commonly used academic accommodations

|

DeMatteo C, Bednar ED, Randall S, Falla K. Effectiveness of Return to Activity and Return to School Protocols for Children Postconcussion: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1).

CBR: consensus-based recommendation; CT: computed tomography; EIR: evidence-informed recommendation; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; GP: general practitioner; LOC: loss of consciousness; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PP: practice point

Algorithm: Imaging & Observation Decision-Making for Children with Head Injuries

Further details to aid algorithm interpretation

1 Always consider possible cervical spine injuries and abusive head trauma in children presenting with head injuries.

2 Children with delayed initial presentation (24-72 hrs post head injury) and GCS 15 should be risk stratified the same way as children presenting within 24 hours. They do not need to be assessed with a further 4 hrs of observation.

3 Remember to use an age-appropriate Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

4 Risk factors adapted from Kuppermann N et al. Lancet 2009;374(9696):1160-70.

5 Other signs of altered mental status: agitation, drowsiness, repetitive questioning, slow response to verbal communication.

6 Severe mechanism of injury: motor vehicle accident with patient ejection or rollover, death of another passenger, pedestrian or cyclist without helmet struck by motor vehicle, falls of ≥ 1m (< 2 yrs), fall > 1.5m (≥ 2yrs), head struck by high impact object.

7 Palpable skull fracture: on palpation or possible on the basis of swelling or distortion of the scalp.

8 Non-frontal scalp haematoma: occipital, parietal, or temporal.

9 Loss of consciousness.

10 Signs of base of skull fracture: haemotympanum, ‘raccoon’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhoea or CSF rhinorrhoea, Battle’s signs.

11 Isolated vomiting, without any other risk factors, is an uncommon presentation of clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI). Vomiting, regardless of the number or persistence of vomiting, in association with other risk factors, increases concern for ciTBI.

12 Observation to occur in an optimal environment based on local resources. Frequency of observation to be 1⁄2 hourly for the first 2 hours, then 1-hourly until 4 hours post injury. After 4 hours, continue 2-hourly as long as the patient is in hospital. Observation duration may be modified based on patient and family variables. These include time elapsed since injury/symptoms and ability of child/parent to follow advice on when to return to hospital.

13 Shared decision-making between families and clinicians should be considered.

14 Do not use plain X-rays, or ultrasound of the skull, prior to or in lieu of CT scan, to diagnose or risk stratify a head injury for possible intracranial injuries.

15 Other factors warranting hospital admission may include other injuries or clinician concerns e.g. persistent vomiting, drug or alcohol intoxication, social factors, underlying medical conditions, possible abusive head trauma.

Special Conditions

Possible abusive head trauma

Follow local screening tools for abusive head trauma (AHT). CT should be used as initial diagnostic tool to evaluate possible intracranial injury and other injuries relevant for the evaluation of AHT e.g. skull fractures. The extent of the assessment of a child with possible AHT should be co-ordinated with the involvement of an expert in the evaluation of non-accidental injury.

Drug or alcohol intoxicated

Treat as if the neurological findings are due to the head injury. Decision to CT scan or observe should be informed by risk factors for intracranial injury rather than the child being intoxicated.

< 6 months of age

Consider at higher risk of intracranial injury with a lower threshold for observation or imaging. Discuss with a senior clinician.

Neurodevelopmental disorders

It is unclear whether these children have a different background risk for intracranial injury. As these children may be difficult to assess, consider structured observation or head CT scan and include the paediatric team that knows the child (parents, caregivers, and clinicians) in shared decision-making.

Ventricular shunt (e.g. ventriculo-peritoneal shunt)

Consider structured observation over immediate CT scan if there are no risk factors of intracranial injury. If there are local signs of shunt disconnection/shunt fracture (such as palpable disruption or swelling) or signs of shunt malfunction, consider obtaining a shunt series based on consultation with a neurosurgical service.

Bleeding disorders or anti-coagulant or anti-platelet therapy

Urgently seek advice from the treating haematology team around risk of bleeding and management of coagulopathy. Consider structured observation over immediate CT scan if there are no risk factors for intracranial injury. If there is a risk factor for intracranial injury a head CT should be performed. If there is a deterioration in neurological status, perform urgent head CT scan.

Coagulation factor deficiency

CT scan or decision to observe must not delay the urgent administration of replacement factor.

Immune thrombocytopaenias (ITP)

Check a platelet count in all patients and blood group in all symptomatic patients if not already available. For ITP with platelet counts < 20 x 109 /L, consider empirical treatment after discussion with the treating haematology team.

On warfarin therapy or other newer anticoagulants (e.g. direct oral-anticoagulant) or anti-platelet therapy

Consider CT regardless of the presence or absence of risk factors for intracranial injury. Seek senior clinician review to inform timing of the CT and discuss the patient with the team managing the anticoagulation regarding early consideration of reversal agents. For children on anticoagulation therapy, if available, check the appropriate anticoagulant measure (e.g. International normalised ratio).